BERTRAND TAVERNIER: You’re exagerrating!

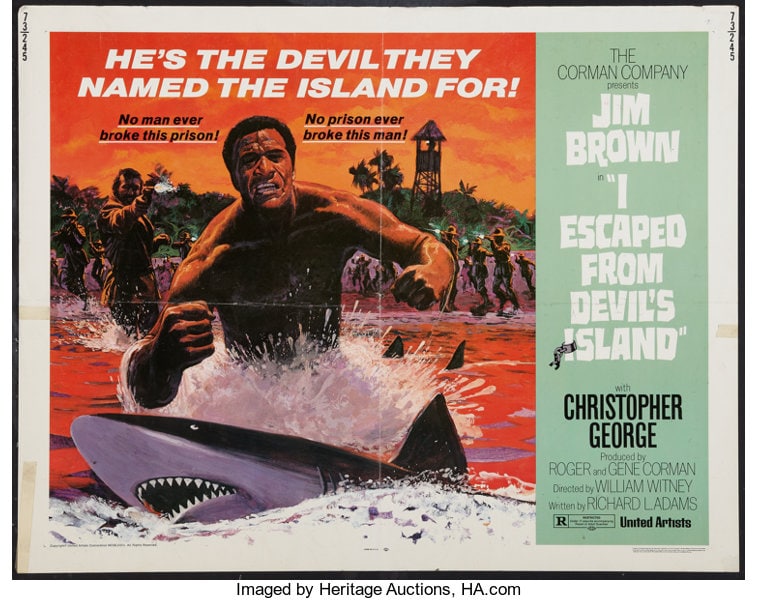

QUENTIN TARANTINO: I’m only talking about the sequences that include Jack Elam. He steals the spotlight from everyone else. He just needs to open his mouth and his replies kill. The best dialogue by Leigh Brackett is for Jack Elam. And when John Wayne fights Victor French, when the legs of the latter catch fire and John Wayne says “Ah, let him burn”, that’s a great moment of cinema, a great moment! What interests me as well, is the work that William Witney was doing at the same time. His penultimate film, I ESCAPED FROM DEVIL’S ISLAND (1973) with Jim Brown, was a strong entry for its genre. It was designed to be a copy of PAPILLION (1973) by Franklin J. Schaffner

BD: I ESCAPED FROM DEVIL’S ISLAND was originally meant to be directed by Gene Corman.

QT: Yea, and he only produced it. He even offered it to Martin Scorsese, but he also refused. It would have been his second film, but Scorsese had his own projects and made MEAN STREETS (1973) instead. I ESCAPED FROM DEVIL’S ISLAND would have been the link between Witney and Scorsese. I’m a big fan of Schaffer’s PAPILLION, I find it a great film that has aged well, but I think that I ESCAPED FOR DEVIL’S ISLAND is just as good!

BD: How do you operate the relationship between Quentin Tarantino the director and Quentin Tarantino the cinephile? Do they live together? Do they separate at any point? Do they fight and have arguments?

QT: That’s a good question! The “two Tarantinos” live together pretty well, but they have to share the apartment with two other tenants: firstly, the orchestra conductor, the one that likes to guide the public. The public is the orchestra and the conductor, that’s me! I want them to do this at this particular moment, that they scream here, that they laugh here, that kind of thing. And when it comes to the second tenant, he’s the one that respects the natural course of things. The people and their proper destinies, destinies that often don’t have anything to do with the canvas that I’ve created. And I always end up going where my characters go. I can always hope that a character does this or that, but once I start writing, they’ll do what they need to do…

BD: The cinephile doesn’t influence the author, and by consequence, the characters?

QT: No, not when it comes to my characters’ motivations. There are things that I would like them to do and if I’m right, they’ll do them. But if I’m wrong, they’ll go in a different direction, and I’ll follow them. It sounds mystical, but that’s how it happens.

BD: In terms of the sources for KILL BILL, a Guardian critic spoke of the dangers of inspiring yourself from any cinema. The question and your cinema asks it, is to know if one must necessarily draw his inspiration in works that are considered minor (B-Movies, comic books) or to search in the sources, for something more “noble”, I’m using sarcastic quotes. He argues that pioneering cinema-inspired itself from the Bible, or great novels, English Russian or French. Where is the frontier? Is it better to be influenced by comic books, John Steinbeck, Elmore Leonard or Shakespeare?

QT: That’s interesting! You know, Bertrand, we are from two different generations. You have your preferences: For example the “mavericks” of the B-movies, from companies like AIP or little departments at Warner and Universal. Mine, there from exploitation companies. What you find sexy in Boetticher or De Toth or even Sam Fuller – even though Fuller walks the lines between all the generations. For me, he is without a doubt the most avant-garde director of them all, excuse my digressions! – so, this sexy side, I found in the films that I saw in theaters, as a child, the ones that moved me or made me shiver, and that seemed different.

BT: Because you have to follow your own path…

QT: Yes, but I don’t exclude all the rest. The great classics, I know them! But honestly, the subversion always comes from the minority. And I defend the messes. When it’s different, when it’s not exactly for the intelligentsia, but for the man on the street and when it’s a more orgasmic way, I’m on it! But Renoir or Hawks are also real artists, tied to sensations that touch an iconoclast public. The directors of B-Movies – in the grandest sense – of all generations offer the same thing: A cheeky little thing that we don’t find in A movies, which gives reason for the B-Movies to exist! You’ll find them more sensational, more exciting, more filled with base excitement, for the same price.

BT: You have passed by Witney or De Toth, no doubt because it’s the cinema of your country, before turning toward Asian cinema, and Italian cinema from the 60s. Wasn’t that way to create a different kind of cinephile, to express something very specific?

QT: I like the cinema of my childhood. Kung fu, is from the seventies, it’s that simple. On my block, the poor block, we grew up with Hong Kong cinema. The access to French cinema was more difficult back then, I don’t know why, so we saw Italian films and Spanish films, uniquely the popular stuff. With the Itlians, the majority were B-movies. And when a Spanish thriller was directed by a great director, it was distributed in America like an exploitation film. Anyway, the border between big public films, auteur films, B-movie, and super production is often very thin. That’s always been the case.

BT: Yea, that frustrated Jacques Tourneur when a journal described him as a B-Movie director.

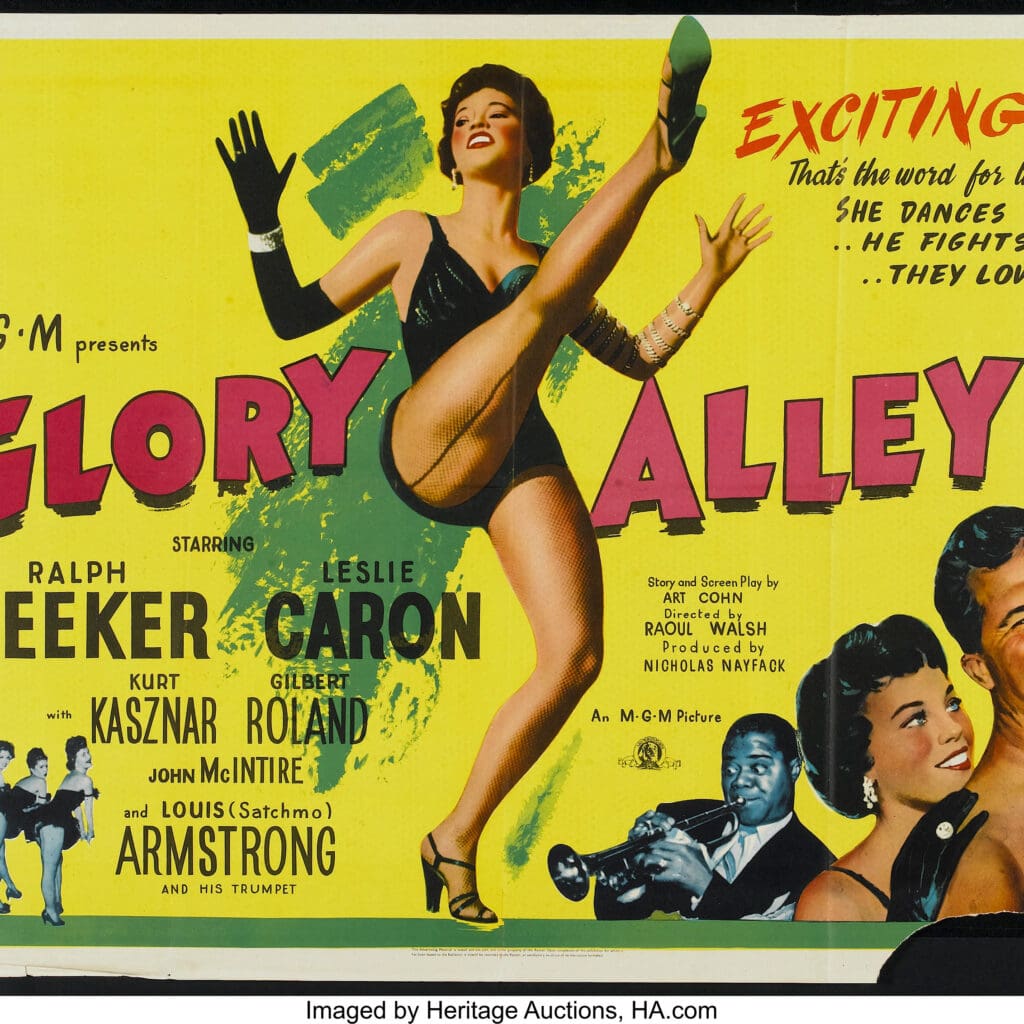

QT: And Tourneur had worked with some of the biggest actors in Hollywood! If you work with popular actors, you’re not making a B-movie and if you’re a great director, no matter what you’re doing, it’s a great movie! When Raoul Walsh made GLORY ALLEY (1952) it was considered an A picture, because it was directed by Raoul Walsh! We talk about it like it was a B movie, maybe because Ralph Meeker stars in it. I love GLORY ALLEY… It’s a great film.

BT: I’m not a big fan of that one…

QT: Me, I love Ralph Meeker. And he’s working with Raoul Walsh… I find that film, from a Hollywood perspective, is very close to NEW YORK NEW YORK (1977). Yea, it gets close to what Marty tried to do.

BT: I want to get back to the article in the Guardian, which discussed this new generation of directors that are inspired by comic books without ever having confronted the cinema of people like Rossellini or Bergman…

QT: When I speak to the public, I discuss the cinema I love. But it’s up to them to decide. Hawks or Rossellini, it’s up the new generation to accept or reject them. And so, it could be Preston Sturges or Jack Hill, William Witney or Lucio Fulci. But it’s the ones that would pass with success this international evaluation challenge that will really love cinema…

BT: In your films, there’s narration that isn’t part of the influences that you claim. For example PULP FICTION, in the irony of its construction and it’s black humour, has something of Billy Wilder…

QT: Now, that’s a compliment! I was reading Andrew Sarris when he was trashing Billy Wilder and John Huston.

BT: Everyone can make a mistake…

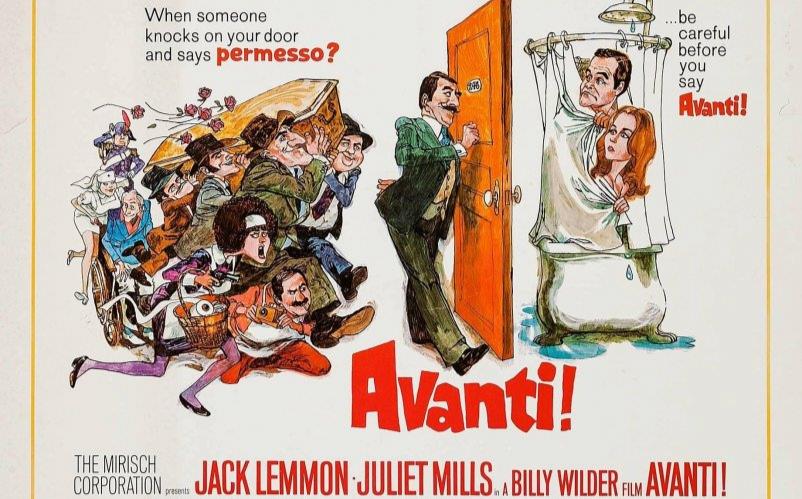

QT: Absolutely! Billy Wilder, that makes me happy. But with him, the one that I would quote, isn’t much of a classic. I discovered last year and I loved it: AVANTI! This film from 1972 is for me the LOST IN TRANSLATION of his generation. I would give nine BUDDY BUDDY and twelve FEDORA for Jack Lemmon lost in Italy. You didn’t remark that at the end of the sixties and the beginning of the seventies, these old filmmakers showed their aging side. Nothing bad in my eyes, it’s even to the contrary: At the moment that we asked them to speed up to face up the young public, they turned it around! When the young public demands speed, John Ford makes CHEYENNE AUTUMN (1964). He shows his age. Well, he was old!

BT: Acting his age was definitely a Ford quality. But in France, we do it rarely, just on principle. The last Renoir, the last Hitchcock, the last Hawks, the last Duvernier aren’t their best films, far from that, compared to the last Huston.

QT: Ah, I’m not a superfan of Huston. Even though I adore PRIZZI’S HONOR (1985), I admit I have little respect for a career that I find too all over the place. If I can’t have confidence in someone, I can’t respect his career. And I can’t have faith in John Huston because too many of his movies are terrible.

BT: But there were films he believed in. And their magnificent, like A WALK WITH LOVE AND DEATH (1969) or THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING (1975). He’s one of the rare directors who had the courage to quit Hollywood just as he was gaining tons of money.

QT: OK, Hollywood life question, John Huston was at the top of the list. His life was great. But he could have been an artist. The poker parties, where he put land he owned in Ireland into play, that’s not enough. It didn’t interest him anymore in being a CINEASTE. He was a macho guy who was more interested in killing elephants or winning at cards than making art. Sorry.

BT: But he still directed THE DEAD (1987) and WISE BLOOD (1979)…

QT: You’re not convincing me, I don’t like WISE BLOOD! So let’s the Huston I really like : KEY LARGO (1948). That’s pure entertainment. You put in the same film Edward G. Robinson, Thomas Gomez, Humphrey Bogart, Lionel Barrymore, you give them great dialogue and it’s very pleasant. Is it deep? No! Is it amusing? Yes! You give me any Italian gangster import from the seventies, and throw in Barbara Rush, and you can count on me, I’ll love it! Is it a great film: no!

BT: I don’t agree with that at all.

QT: But I love PRIZZI’S HONOR! My cinephile friends used to joke about that when I saw the film, I complained “My god, Huston is going to die soon and he starts to make good films! It’s going to ruin everything, he has to make another film! He can’t die now!!!!”

BT: Let’s change the subject. When you’re on set, do you watch films?

QT: Yes, but not films that are related to the subject that I’m filming: those ones, I’ve already seen them. Let’s say it’s Friday night, it’s 8:00 PM, the shooting day has finished, and a film comes out that day, I’ll check it out at midnight. But it’s gotta get my attention, because it could my own rushes I was watching on-screen! Up until now, only three movies have passed that test 110%. When I was filming PULP FICTION, I loved DAZED AND CONFUSED (1993) by Richard Linklater. When I was filming KILL BILL in 2003, two horror films caught my attention: FINAL DESTINATION 2 by David R. Ellis and FREDDY VS JASON that knocked me off my feet, but I’m a big fan of Ronny Yu, especially of THE BRIDE WITH WHITE HAIR (1993) which I really love.

BT: At home, do you watch films on 16mm or on DVD?

QT: I have an irreplaceable collection. Otherwise, I really love laserdiscs, with the players, the cases, the discs. I didn’t abandon them, but I realized that DVD is the better format.

BT: G-MEN VS BLACK DRAGON by Witney, exists on Laser

QT: I know! On the same disc as ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL (1941)

BT: There’s also THE DRUMS OF FU MANCHU (1940)

QT: Absolutely! That’s one of the greatest serials of all time, with Henry Brandon, who does the best Fu Manchu ever! Even better than Boris Karloff or Christopher Lee…

BT: And the first episode is brilliantly directed.

QT: A-MA-ZING-LY directed!

BT: Are you someone that makes discoveries? Do you verify your judgements?

QT: Yes. The DVD is great for genre cinema, like the Spaghetti Western. There, I’m spoiled. Before the arrival of video, I had read the book by Tony Williams and Laurence Staig, Italian Western: The Opera of Violence, and I was dying to see those films. I was able to catch a few in theatres. The DVD editions have put cinema in perspective, we can really get our hands on those films. When it comes to giallo, the Italian mystery film, there’s so many we can really form an opinion. For your critical sense, it’s extraordinary. And you can complement the work of a director that you had previously seen only one film that they made.

BT: Sergio Sollima, for example?

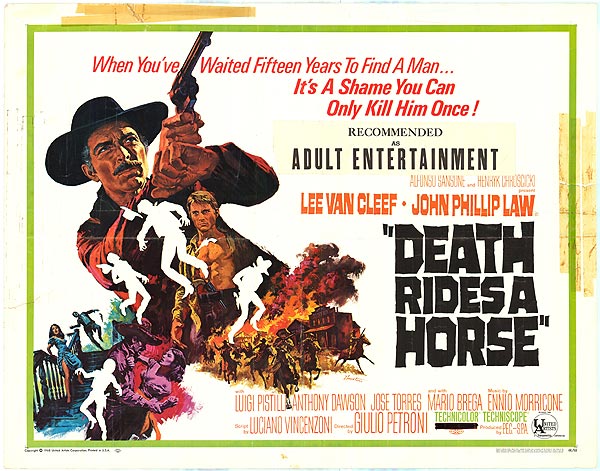

QT: Not everything has the same value, but THE BIG GUNDOWN (1966) is on its own. I didn’t know him very well, but now I’ve been able to see his other films, I know which are the best. It makes me think of Giulio Petronic, the author of DEATH RIDES A HORSE (1973), his best film. In Venice, when I did a retrospective with Joe Dante of Italian B-cinema, a critic decided I took stuff from DEATH RIDES A HORSE into KILL BILL, like the revenge theme. They also said that Giulio Petronic was inspired by THE BRAVADOS (1958) by Henry King. So the critic proudly presented his equation: “On one side, Peteroni took some stuff from King, on the other, Tarantino took from Petroni: Did Tarantino know that Petroni borrowed from King?” Maybe yes yes, maybe no.The real thing to take away from this is that there are all fingers on the same hand.

BT: THE BRAVADOS was underrated when it came out.

QT: Which was a mistake, it’s a formidable film which A FEW DOLLARS MORE (1958), which I saw first, took a lot from: Lee Van Cleef, the medallion, the photo of the medallion, the revenge, the murder fro the medallion, everything! Did you know Sergio Leone is my favorite director, the one that influenced me the most, but it’s A FEW DOLLARS MORE that entered into legend and not the original scenario! At the same time that Leone was borrowing from YOJIMBO (1961) to make A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS (1964), but he did it more simply, more efficiently. Personally, I prefer Kurosawa’s version.

BT: So, it is with the Italian western that DVDs have been most useful to you?

QT: Yep, in one fell swoop, a bunch of forgotten films became accessible. When one film came out, we could fantasize about a director. Now, we can’t make errors anymore. Take Gene Martin for example, the Spanish director: If you just see BAD MAN’S RIVER (1971), you only know a middling Spaghetti Western, you may think he’s the worst director that ever lived. But if you see THE UGLY ONES (1966) with Tomas Milan, you can also say that’s the best movie ever made! He also directed HORROR EXPRESS (1973) which is magnificent…

BT: Written by Bernard Gordon, a blacklisted writer.

QT: Yep! At the time, all I knew was BAD MAN’S RIVER (I saw it at the drive-in when I was a kid) and I didn’t hold him in very high esteem.

BT: That says a lot about the state of cinephilia. Thanks for the fervor of fans, Italian genre cinema is very available on DVD. The films of Mario Camerini, of Vittorio De Sica, of Pietro Germi, of Mario Monicelli, of Dino Risi, or of Luigi Comencini pale in profile compared to to the giallo or the spaghetti westerns. In their time, the two kinds of films coexisted in cinemas. Now, one is better represented than the other. Like, ACT OF VIOLENCE (1948) by Fred Zinnemann, an amazing film, is unavailable on DVD, while you can buy Jess Franco’s A VIRGIN AMONGST THE LIVING DEAD!

QT: I can see where you’re coming from and I partly agree. I would just say that it’s been thirty years where the directors took seriously where the ones that your generation chose. It’s our turn to have a chance in the sun! I’m not saying it’s the end for the others, I’m just saying that the moment has come for the Italian B-movie director to represent Italian cinema. When he published Spaghetti Westerns: The Good, The Bad and The Violent, the critic Tom Weisser did his work (TRANSLATOR NOTE: Tom Weisser did not do his work. His books are infamously filled with inaccuracies and fake entries). There are still directors like Calvin Jackson Padget (Georgio Ferroni), who for me, is one of the best examples of a director in the sub-genre. He made films about the civil war like no one had ever done in American cinema. On the specifics of the union and confederacy, he made at least four films. And they’re not recognized. During the laserdisc period, we could easily find MIRACLE IN MILAN, but it was impossible to see giallos or spaghetti westerns. I had to go to Japan to see A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL (1966) by Damiano Damiani on laserdisc, which I found disappointing.

BT: I agree with the idea that all genres should be represented, but films shouldn’t disappear…

QT: When I go to the international section of a store, I find films that were previously unavailable. Now, Asia is in style and it deserves it.

BT: But that concerns just a part of Asia. The best directors from South Korea, for example, are never shown here, or the United States. Same for Latin American filmmakers, Brazillian cinema, Mexican cinema, and Argentinian cinema is difficult to see

QT: Yea, but Alex de la Inglesia is known thanks to DVD. Just like Takashi Miike, who is as popular as a rock star, thanks to four or five films, while he’s made forty .

BT: True. But, if I could be the devil’s advocate…

QT: We’re both devil’s advocates. It’s a debate between devil’s advocates!

BT: …I would say that the reason that Samuel Fuller or Budd Boetticher were rare and undervalued, was because they represented a certain counter culture. Today, their modern parallels are part of the dominant culture, plugged in, and in fashion..

QT: … Which is a problem, because it goes against the nature of cinema.

BT: Roger Corman was counter-culture and he was brilliant. His successors tended to become figures of the dominant culture versus the minority. It’s worrisome to see the American Cinema start to go the way of the comic book. I love a lot of them, like SPIDER-MAN 2 (2004) by Sam Raimi for example, there’s no question there. But the niche is becoming mainstream.

QT: What separates the B-movies of today from the A-movies today, is the scripts. There’s a giant gap. In the first half-hour, we just gave you what was necessary and you knew there was more to come! The story could go in all directions as it went along and there would be turns and reversals. And the story could end differently. And I’m not talking about scripts written by ‘auteurs’, I’m talking about B-movie westerns! A scenario shouldn’t reveal everything right at the start, but have layered reveals. An interesting story has reversals and surprises, and the end is different from the start! In popular American cinema, we are currently in what I call situational films. We plan a situation, or the premise of a situation, and good films follow that track. They stick to that path. In the first ten minutes, everything is presented “Here is what we will offer you.” There are tons of good films, there’s no doubt. But the linear films of the fifties and sixties feel modern today. A film like THE LAST VOYAGE (1960) by Andrew L. Stone is a very good example.

BT: What you say is true. The difference is that prestigious films were directed by artists like George Stevens, Fred Zinnermann, William Wyler, Billy Wilder, who were their own masters. John Ford, Frank Capra themselves decided what movies they wanted to make. You also had people like Henry King, who had won certain liberties thanks to their relations at the heart of the cinema and could make a series of very personal films. On the other side, you have B-movies made by people that were very talented. I think of a dialogue writer like William Bowers, who wrote SPLIT SECOND (1953) by Dick Powell, CRY DANGERS (1951) by Robert Parrish and PITFALL (1948) by Andre De Toth. Those films had orgasmic scenes, like you say. And we took their subjects as destined for the general public. Though, they were “produced-directed” by the studios that were obsessed with box-offices a la mode and there aren’t any Daryl Zanuck, or Harry Cohn, who were real cinephiles.

QT: You just said something significant. You cited SPIDER-MAN 2 and not 1. In SPIDER-MAN 1, the first part is successful. You could tell that the director had grown up reading the original comic book. We get that feeling because Sam Raimi really loves Spider-man. The Comic book. The second part of the first film is just a superhero film. In comparison, SPIDER-MAN 2 is all good. You know why? The first part brought in enough money to give Sam Raimi the permission to do whatever he wanted with the second one. And he did even better.

BT: GREMLINS 2 (1990) is also better than the first one.

QT: Oh yes! Largely! For me, GREMLINS 2 is all Joe Dante. It’s like the Chuck Jones film that was never made. Isn’t it?

BT: Absolutely!

QT: In the same way that Chuck Jones did some Joe Date, Joe Dante did some Chuck Jones. And at the same time, it’s a very personal film. Even if for me, EXPLORERS (1985) is his most personal film.

BT: In invoking before the moguls of the studio system era, I’ve always heard Andre De Toth speak positively of Harry Cohn, who had an awful reputation. In some ways, you’re in the same situation with Harvey Weinstein…

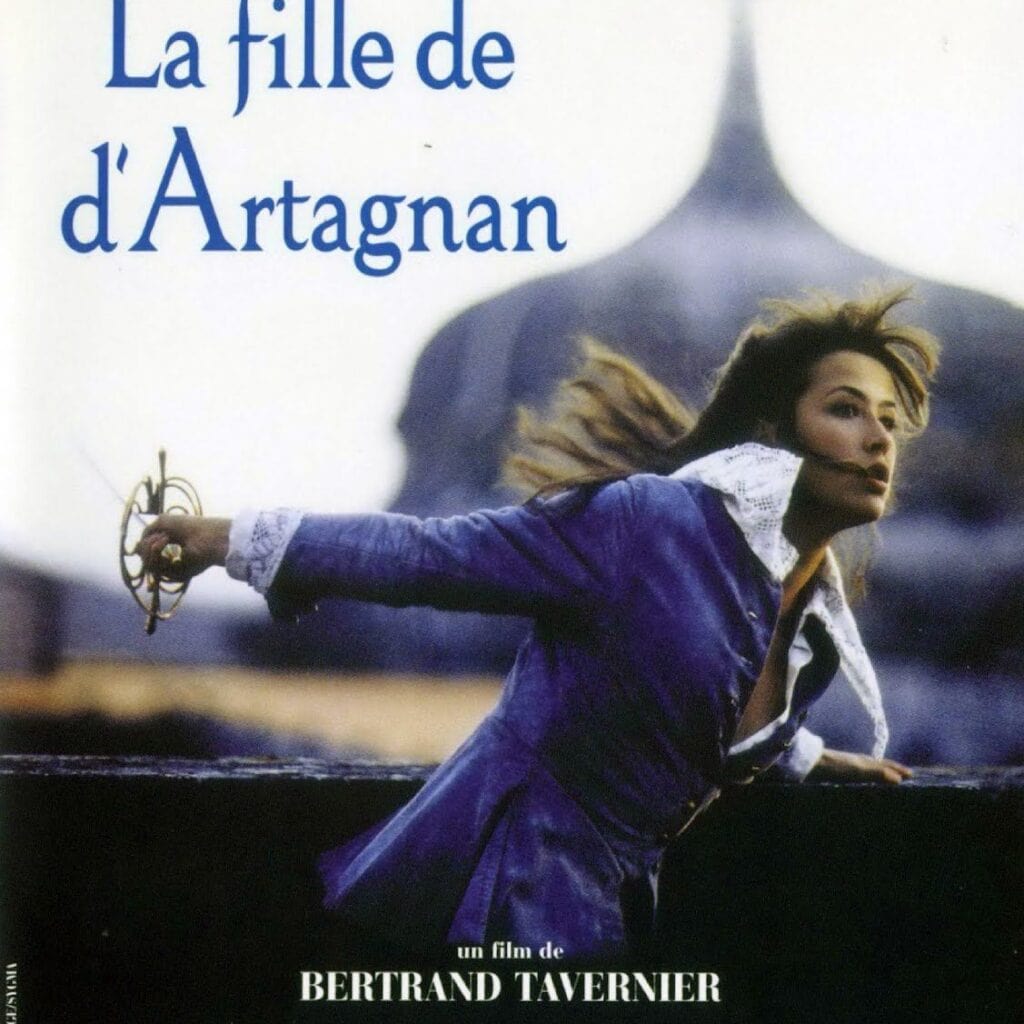

QT: Yea, it’s the same way. Like Sam Fuller with Zanuck! Boy, I know he made you suffer with the American release of THE DAUGHTER OF D’ARTAGNAN…

BT: Bah, I just felt like a slave in the system! But anyway. Like Harvey, Zanuck could be an asshole, but Jules Dassin told me that he could also be a protector and a creative. That’s missing from today, no? Today, the credits of an American film featured a dozen different ‘producers’…

QT: I’m not going to sell you Harvey Weinstein. Me, he takes my work as is. If I do good or I do bad, he supports me. Evidently, I know he can act like a real asshole. I just fell on his good side. He’s one of the rare filmmakers of this century that acts like Zanuck or Harry Cohn. He is not a bureaucrat who does his work and fires people to find better replacements somewhere else. When he receives my script, he reacts to the emotion. It puts him on the level of producers like Sam Arkoff, the ones who make decisions with their heart, their gut, or whatever you want! It seems like one thing we tell to you filmmakers now is: “We want you to be what Tarantino is to Miramax!” And a few reply with “Start with by Harvey Weinstein.” Because often, the producers are there for the strict minimum, shaking in fear of being fired at the smallest disagreement with their boss.

BT: Do you have final cut?

QT: Yes. I didn’t have it on RESERVOIR DOGS (1992), but I got it. The edit of the film is mine. On PULP FICTION, the majority investors were TriStar and Danny De Vitor, who was the producer with Lawrence Bender, officially had the final cut, because according to him, they didn’t want to give it to me. When Tristar dropped it, Miramax entered into the dance, and from there, I was free. And it hasn’t changed since.

BT: You learned to gain your freedom?

QT: I’m the screenwriter of film films, which makes a difference. The artistic process is how I conceive it, and it’s what I’ve written. I’m not a director that searches out a script or who waits for a script that will excite him. I go first to my own writing. And it takes the time it’ll take. Writing and directing is part of the global aesthetic of my work, not to be pretentious. What happened in the old system, except for Joseph Mankiewics or Billy Wilder, doesn’t apply to me. If I wasn’t a screenwriter, I would be known for championing a good script, in the way that the directors of that era were able to do. Not as much as being an author, because creating is imaginary, and it makes you a reputation. But if after RESERVOIR DOGS, some people said: “With good scripts, while keeping his aesthetic, he could make us a success.”, that would have been my career and I would have accepted it. But PULP FICTION made money, without concession or compromise. I could have maybe done good work with someone else’s script. If I was obliged to make a film for a studio, I would have made a hell of a film, believe me! But that’s not how it happened. And my own films, the way I wanted to make them, is the best thing that could happen to me…

BT: You took a lot of time between JACKIE BROWN and KILL BILL…

QT: For a moment, I became too famous, sorry to say it like that, and I had to reconnect my own cinephilia. Not on the superficial aspect, but into world cinephile, for my own truth. I had to go back to my origins. I was so publicly defined by my love for cinema that it didn’t belong to me anymore. As if I had sacrificed everything that had made me. It’s then that I told myself: “I will forget I became a filmmaker and I will return to being a cinephile. I pretended I was never going to make another film and I became a sort of author-critic. It’s KILL BILL that got me out of all of that. I’m a cineaste-cinephile.

Tarantino has a lot of interesting thoughts but his general problem is he comes at movies like a child. Basically just talking up trash because he grew up with it. Some of it is GREAT, but he’ll act like some garbage tv movie is amazing or a bad Italian shark movie is worth watching.